Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey embraced the role of outsider during prestigious fellowship with the Africa-Oxford Initiative at the University of Oxford

Standing in a centuries-old lecture hall at the University of Oxford among some of the world’s brightest minds in refugee studies, Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey is a standout.

With six degrees from universities on four continents, the Athabasca University researcher has earned her share of accolades for her work in law, human rights, and social justice, which included an invitation to Oxford as a visiting fellow through the Africa-Oxford Initiative at the university’s Refugee Studies Centre.

Even among such accomplished peers, Fynn Bruey was the only academic with both research and lived experience in refugee studies as an Indigenous Liberian, a war survivor, and a migrant to Canada.

“The way it works in academia when it comes to refugee studies is you have white people studying the suffering of poor Black people or people from the Global South and theorizing and philosophizing about their lives,” she explained. “I have both. I have the academic credentials, and I have the lived experience.”

That distinction has not only heavily influenced Fynn Bruey’s life and her research, it also impacted her experiences during the six-month visiting fellowship, which wrapped up this past December.

Great honour to receive fellowship

Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre is internationally renowned for attracting top researchers to advance understanding of the causes and effects of forced migration. Fynn Bruey’s work at AU and as president of the International Association for the Study of Forced Migration made for a natural connection, she said. A colleague recommended her for a visiting fellowship—a prestigious honour that typically sees more than 500 applications for 22 total spots. Fynn Bruey had previously applied and missed out, so getting accepted was a pleasant surprise.

I was very humbled and pleased and honoured—and very grateful.

Surviving civil war in Liberia

Fynn Bruey said part of that surprise is due to the “chronically low” self-esteem and imposter syndrome that she’s felt throughout her academic career, and in her earlier life.

Growing up in Liberia in a mud house with dirt floors, she never had access to books, and yet learned of the value of education from her mother, who went to night school to earn a high school diploma even after becoming pregnant.

“She always told me, don't ever end up like me. I certainly did not disappoint her,” Fynn Bruey said in a 2024 Black History Month panel organized by the Athabasca University Students’ Association.

When civil war broke out in 1989, Fynn Bruey became a refugee at the age of 13. As she told the Law and Society Association in a 2020 interview, her life was suddenly in limbo as she was forced to flee by foot, sometimes alone, in search of safety.

“When I returned home in May 1991, our house was destroyed, so I had to perch around until my mother and siblings returned in October,” she said.

Fynn Bruey’s path to academia started the following year after she was evacuated on the deck of a Ghanaian peacekeeping ship that took her away from the war zone, but not necessarily to safety, as refugees were often victims of sexual and physical violence.

Though she earned her first degree from the University of Ghana in 2000, her academic journey and arrival in Canada was marked by persistent racism and gender discrimination, and even a period of homelessness after arriving at the University of British Columbia in August 2001.

I arrived in Canada with $20 U.S. dollars and two suitcases as a refugee sponsored student.

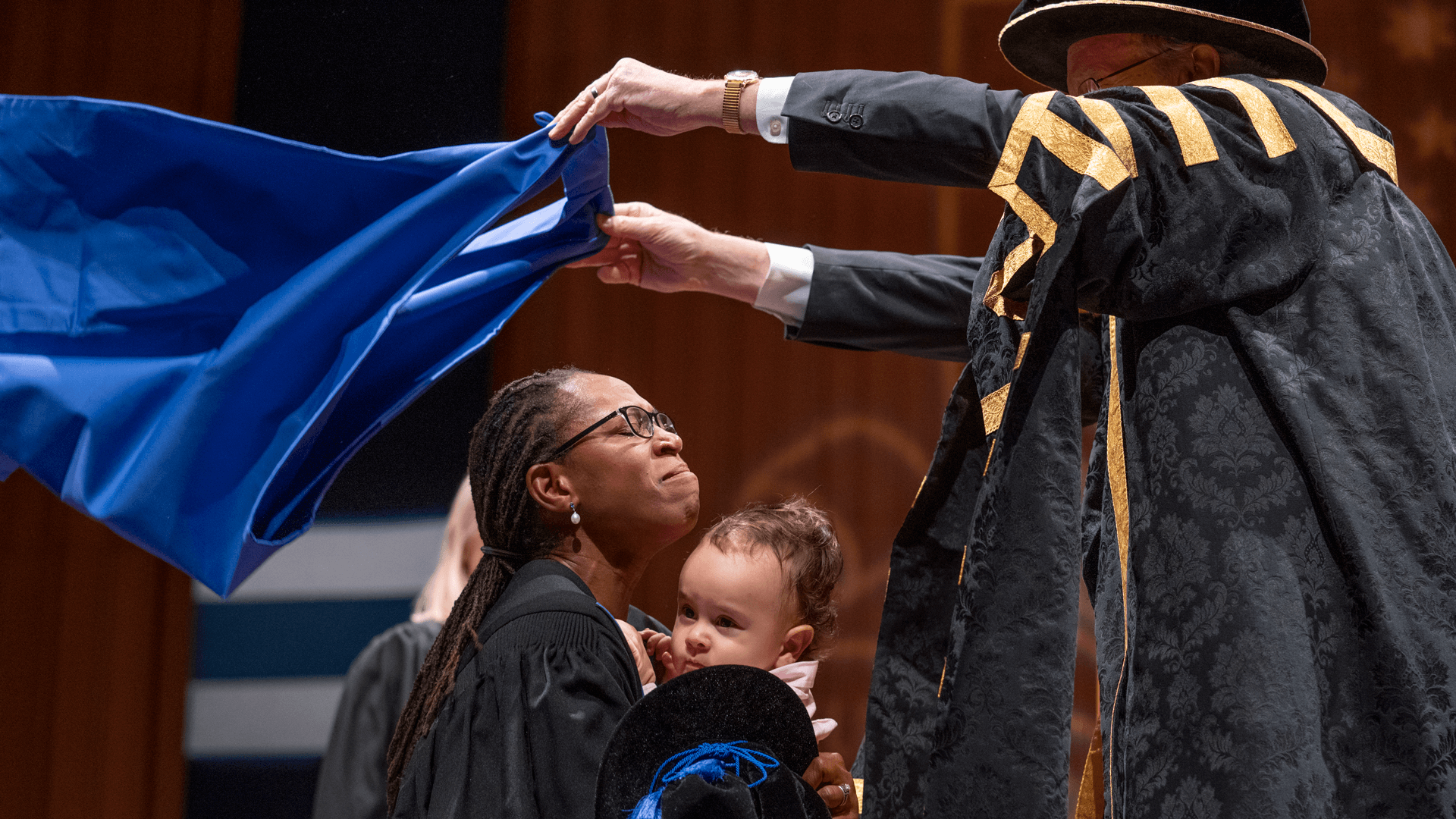

Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey, holding her son, receives her ceremonial hood to commemorate her doctorate in Indigenous studies from Australian National University in 2019. The ceremony occurred 30 years after civil war prompted her to flee her home in Liberia. Image: Lannon Harley/Australian National University.

Journey in academia

As one of only two people of colour in UBC’s psychology program at the time, she said she never saw another Black person until the end of the day when she’d watch TV in her dorm room. Even then, the images she’d see of life in Africa were of malnourished children and criminals on the news, she said during the AUSU talk.

“I stopped watching TV. To this day, we don’t own a TV.”

During a 2010 visiting scholarship to Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, D.C., Fynn Bruey, who by this time had earned a handful of degrees, received an unsettling email from the program director telling her she wasn’t cut out for academia and would be better off working for a non-governmental organization.

“I was given one week to voluntarily withdraw from the program or face expulsion,” she recalled. “I’ve never cried so much in my life.”

“For me, acquiring six degrees across four continents and travelling the world and becoming visible in a space where I'm supposed to be invisible … it propelled me into that space of being attacked more.”

Flipping the script at Oxford

As much as she was honoured by the invitation to Oxford, Fynn Bruey admits she also felt like an outsider at Brasenose College, which she called home during her fellowship. But she also embraced the role of outsider when choosing her research topic.

As much as she was honoured by the invitation to Oxford, Fynn Bruey admits she also felt like an outsider at Brasenose College, which she called home during her fellowship. But she also embraced the role of outsider when choosing her research topic.

As an Indigenous Liberian and war survivor, the focus of her research is on the displacement of transnational Indigenous Peoples. She intended to study Indigenous displacement in England and its impact on the Irish, Welsh, and others. But after experiencing the “entrenched colonial systems” of class and hierarchy at Oxford, she decided instead to explore the violence of medieval England and evolution of legal protection of survivors, especially women and children.

Fynn Bruey said researchers at institutions like the Refugee Studies Centre “always love to look at the Global South” and war happening in Africa, Asia, or South America and cast judgment on the violence and “primitive” behaviours of local populations. This was an opportunity to turn the tables.

“You've been researching poor people from Africa forever. This is my turn to research your violence. You have wars here too—and if anything, you had one of the most violent cultures ever in medieval England.”

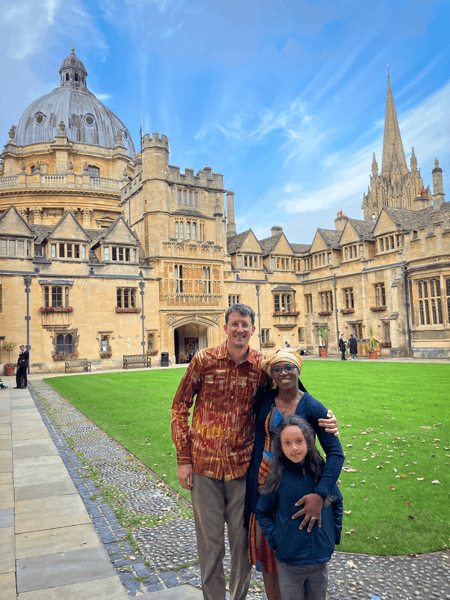

Above image: Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey with her husband and son at Brasenose College at the University of Oxford.

Related: Displaced Peoples research network

Violence is a human condition

Though the 900-year-old institution’s libraries contained a trove of information about medieval England, it was challenging to find information about how women, children, and others were protected in the face of brutal violence. “Most of the time, they ended up killing a lot of people, or when they captured them, they also used them as slaves.”

Fynn Bruey said she received plenty of helpful feedback when she presented preliminary findings at the Refugee Studies Centre, but not everyone was impressed with her line of inquiry. At one point, the woman moderator declared: “I’m going to stop all the men from speaking now,” so that the AU researcher could finish her talk.

“They told me, ‘You can’t do that because it’s not the same as now. You can’t compare protection of refugees in those times to now.’ And I’m like, you have for centuries! Those of us from the Global South and with lived experience, our views are never welcome … it's seen as subjective, not critical enough.”

Empowered back home in Alberta

Fynn Bruey said reaction wasn’t all negative, as she had productive conversations with several colleagues, including an accomplished expert in the violence of medieval England. She came away from the experience feeling empowered.

Now back home in Alberta, the plight of refugees in medieval England is not entirely a focus of her work at the moment, but she’s grateful for the experience and for the opportunity to make a larger point about how academia views refugee studies and Black academics.

“I can have that power to say that, England: you were also violent. It's a human condition. That's all I want to say. So don't label people. Don’t stereotype a certain group of people and call them uncivilized and primitive because every human being is capable of being violent.”

Learn more about Dr. Veronica Fynn Bruey on her blog and discover her research

A university Like No Other

Athabasca University is a university like no other, uniquely focused on the core priorities of access, community, and opportunity.