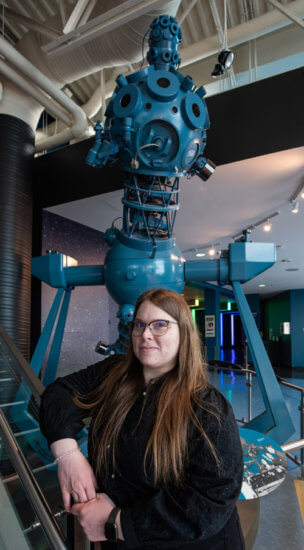

Natasha Donahue helps bridge gap in science education for Indigenous learners

By age 8, Natasha Donahue (Bachelor of Science '21) already knew she wanted to be an astrophysicist. But that dream lay dormant for 20 years, stifled by the challenges she faced as a Métis woman, a high-school dropout with a learning disability, and then a single mother.

With an education at Athabasca University, Donahue stirred her childhood dream back to life.

Today, she holds a bachelor of science degree and works as an Indigenous educator with the TELUS World of Science in Edmonton, where she applies her passion for astronomy and physics to help open young minds to the possibilities of science.

She is also a research assistant in astronomy at AU, and a member of Harvard University's Galileo Project, an international research initiative to search the cosmos for evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence.

Donahue is one of thousands of Albertans for whom AU has provided a launchpad that practically no other post-secondary education can rival.

"There are a lot of people who would never be able to attend a traditional university," she says, "and I would count myself as part of that demographic."

From high-school dropout to rekindling lost dreams

Despite her early ambition, high school was challenging. She dropped out before graduating and took a job at a fast-food restaurant. She was there for nearly 8 years and did well, eventually working her way up to assistant store manager. But something was missing.

"I kind of lost that dream," she says, "and I had convinced myself that it would never be possible."

Donahue moved on from the restaurant business, eventually starting a dayhome. Working with young children every day-and sharing her interest in science with them-made her "remember the 8-year-old version of myself again," she says.

"I realized that this is something I love, and it gives me energy and joy, and I decided it was time to think about going back to school."

Following a dream from rural Alberta

Newly single, raising a family and living in the small community of Barrhead, north of Edmonton, Donahue found her options limited. But an uncle who had studied at AU recommended it.

"He said, it's anytime you want, anywhere you want, and I thought that was pretty cool," she recalls.

After upgrading a few high-school credits, she began pursuing a bachelor of science in 2013.

Initially, she found studying at the university level "a lot more difficult" than expected. But AU's flexible, customized approach helped: In most cases, the school sent lab kits straight to her home, and faculty members were understanding and accommodated her learning disabilities.

Donahue has anxiety and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sometimes needed extra time for assignments or private exam spaces so she could focus. At one point, she was able to take a year off and occasionally put courses on hold to fit her schedule.

She was able to take a year off at one point and occasionally put courses on hold to fit her schedule.

Depending on what was going on in my life, I got extra support. AU was very welcoming and open to helping.

Natasha Donahue

"Depending on what was going on in my life, I got extra support," she recalls. "AU was very welcoming and open to helping."

That flexibility also allowed Donahue to deepen her involvement in issues she cares about. She joined the AU Students' Union executive and in 2020, was elected president. She volunteered at the University of Alberta's Let's Talk Science youth outreach program, and served as a science education facilitator at Moving the Mountain, a program supporting young Indigenous women at risk in a holistic, alternative educational setting.

Bridging gap in science education for Indigenous People

That work encouraged her to take elective courses on Indigenous history and culture, and she found in them a cause: to bridge the "big gap" in science education for Indigenous People. In traditionally Eurocentric scientific thought, Donahue says, "their worldview is just not represented, and there's a huge lack of resources and tools to support them. It's a big can of worms to open, but we have to open it."

Since graduating in 2021, Donahue has directed her energy towards addressing that challenge. As a member of the steering committee for the Galileo Project, she helps develop policies and programs that respect Indigenous communities.

[Indigenous] worldview is just not represented, and there's a huge lack of resources and tools to support them. It's a big can of worms to open, but we have to open it.

Natasha Donahue

As an educator, she talks about Indigenous "concepts of thinking holistically and examining the interconnectedness of all that exists, really focusing on our connection to the land and the sky and everything around us."

A self-described "lifelong learner," she hopes to pursue further studies on Indigenous approaches to science and their potential to advance scientific thought.

"I want to encourage people not just in Alberta or Canada, but around the world, to bring their knowledge and wisdom to the table."

Helping others unlock their potential

That, in many ways, is the value of Athabasca University, she says: to help people bridge the barriers to advanced education and unlock their potential.

"If we don't support people who have careers but would like to pursue different paths, or people whose circumstances aren't conducive to going physically to a university, then we are creating a lot of wasted opportunity.

"Those individuals have talents and skills and perspectives that are so important to our world. And now, more than ever, we need that diversity."

Open for Alberta

Read more profiles of AU learners and grads in our Open for Alberta series.